Symposium 2023

The third symposium of the Belgian Network of junior Researchers in international law took place at the ULB on the 30th of May 2023. It allowed early stage researchers to present their PhD topics to an audience and gather insightful commentaries from experts such as Olivier Corten (ULB) and Luca Ferro (UGent).

We had the chance to hear Mathilde Brackx exposing issues of enforcement of human rights litigation against transnational businesses. Karel Brackeniers presented the problematic of secrecy and access to documents as a researcher in the field of U.S. nuclear sharing. Finally, Begum Kilimcioglu explored the use of private international law tools to prevent human rights impact of environmental harm in global value chains of the extractive sector.

Transnational Business and Human Rights Litigation: What about Enforcement?

Economic and supply chain globalisation have had both positive and negative consequences. Negative consequences include companies’ adverse impacts on human rights and the environment through their activities and in their supply chains. Providing access to remedy for victims of such adverse impacts has proved to be a persisting challenge. Transnational civil litigation against companies is one possible – and increasingly relied on – road to such access to remedy. These transnational civil proceedings raise questions of private international law, including on the cross-border recognition and enforcement of judgments, which is an indispensable part of the right to access to justice.

This research project examines the possible hurdle of cross-border recognition and enforcement of judgments in transnational civil business and human rights litigation, both in theory and in practice. It consists of an analysis of the legal framework of private international law rules on the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments on the one hand, and in-depth case studies into specific transnational civil proceedings against companies on the other. This will enable an assessment of the extent to which this legal framework on cross-border recognition and enforcement of judgments is adequate to provide victims of corporate human rights abuse with access to remedy.

Introduction to Issues in Researching U.S. Nuclear Sharing

Secrecy seems at first sight to be antithetical to law. Law and its study require a clear view of which rules are in force and which procedures are relied upon. Nevertheless, a lack of clarity, through contradictory, vague or secret norms, can arise purposefully through coordinated government action. Though classification and other secretive measures protect sensitive information, they are also a very sharp double-edged sword capable of stifling public debate and protecting governments from scrutiny.

This ‘executive secrecy’ perfectly dovetails with an executive’s foreign affairs powers. Though parliamentary scrutiny and (in some countries and to very differing extents) judicial scrutiny are often guaranteed in (constitutional) law, the practices of executives both in the past and present can limit such scrutiny. In the international legal field secret treaties and secretive executive agreements persist, despite article 102 UNC and article 80 VCLT.

A specific case study of the dovetailing of unilateral executive action in foreign affairs and executive secrecy (and, arguably, the summum of historical secrecy) presents itself in the practice of nuclear sharing. Beginning in the 1950s the United States ‘shared’ its nuclear weapons with allied countries around the globe through a host of agreements that remain understudied. The study of (post)secrecy in general and nuclear sharing specifically raises unique challenges and requires a mix of legal research methods. This project proposes a combination of doctrinal constitutional, foreign affairs and international law research, as well as archival methods.

Investigating the Use of Private International Law Tools in Preventing Human Rights Impact of Environmental Harm in Global Value Chains of the Extractive Sector

My research aims to investigate the use of private law tools (codes of conduct, contractual clauses, and reporting mechanisms) in preventing the human rights impact of environmental harm in the value chains of the extractive sector. Preventing harm rather than remedying proves to be the most important, considering that most of the time, human rights and/or environmental harm are irreparable. The extractive sector is the perfect sector to observe the human rights impact of environmental damage, as the extraction and production activities closely relate to both. There has been a growing interest in regulating the behavior of corporations in the last few years. Such regulation efforts started as voluntary measures. However, in time, seeing that the voluntary measures did not prevent the harm caused by the corporations, the world has shifted in approach to obligations. In this regard, some countries started to adopt hard laws, and the European Union has also started to work on the matter. Consequently, there emerges a need first to identify and describe these new developments and contextualize how these different new developments will come into play and interact to induce change in corporate behavior. My research aims to find the answer by comparing and evaluating how different jurisdictions, i.e. the EU (France & Germany), the United Kingdom, and South Africa, have addressed the issue. I will also investigate the uptake of these duties by businesses in the extractive sector.

Symposium 2022

The second symposium of the Belgian Network of junior Researchers in international law was organised at the KULeuven on the 12th May 2022. The theme chosen was « Method and Methodology in International Law ». Different members of the Network were then invited to share the challenges they face regarding these issues in their own research.

Among others, ways to include different theories of international law in a thesis (Thomas Van Poecke), the handling of decisions from domestic courts (Stefano D’Aloia) and the challenges of comparative studies between the approaches to international law from different countries (Sebastiaan Van Severen – not published) were discussed.

We had the chance to see Professor Gleider Hernandez offering to the participants his excellent comments.

Warriors or Terrorists? The Transnational Criminal Law Framework on Activities of Non-State Armed Groups and their Affiliates related to Armed Conflict

I start from the traditional assumption that it is possible and valuable to distinguish between what the law is (lex lata) and what it should be (lex ferenda). Accordingly, the starting point is positivist, as positivism is the only theory of international law that cognizes the law as it is rather than as what it is not or what it should be. However, in light of the post-modernist acquis, positivism can no longer insulate itself from criticism and input from what it has typically framed as the ‘outside’.

The reductionist version of positivism acknowledges that law is a social practice and that legal interpretation is ‘geared towards persuasion, whose validity hinges on the recipient epistemic community’. Within this community, there may not always be agreement on what the law is or should be, but there is agreement on the law-ascertaining criteria; agreement that is presently centred around the doctrine of sources.

A meaningful analysis of international law requires input from other theories. I rely on Koh to conceive the legal framework that I study as a reflection of a ‘transnational legal process’. The framework is created, interpreted, applied and changed in a dynamic and iterative process that involves state as well as non-state actors at the international, regional and national level. This theoretical perspective allows me to see and understand how the law as it stands took shape, and which actors and processes can change it.

Finally, I use ‘human dignity’ as an overarching criteria for the normative part of my analysis on two theoretical bases. First, within the epistemic community, there is wide agreement among law-makers, judges as well as scholars following ‘traditional approaches’ to international law that human dignity is a fundamental meta-legal concept, principle or value. Second, the ‘New Haven School’ of policy-oriented jurisprudence finds that law should be used ‘to achieve progress on the road to a new world order based on the fundamental value of human dignity’.

In terms of methodology, I start with a historical analysis of the international law on the relation-ship between terrorism and international humanitarian law (IHL), focusing on how states’ con-flicting interests have coalesced into law that is characterized by ‘constructive ambiguity’. Second, I analyse how this law was implemented at the regional and national level, which in turn improves understanding of how the law is seen across the globe. Third, I conduct a comparative case study of how Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands deal with activities of non-state actors and their affiliates related to armed conflict. Relatedly, I conduct expert interviews with legal practitioners (public prosecutors and defence lawyers) in these three countries. Fourth, I insert relevant input from human rights law into the analysis of the relationship between terrorism and IHL. Fifth, I examine insights from social science research (e.g. on victims’ needs). Based on my comparative findings, input from human rights law and primary and secondary data, I substantiate the concept of human dignity and use it as a benchmark to evaluate and improve the legal framework.

The duty not to recognise the consequences of a serious breach of a jus cogens norm

The purpose of my research is to determine the scope of the duty not to recognize the consequences of a serious breach of a jus cogens norm (art. 41, par. 2, ARSIWA). Whereas it is widely admitted that such a duty has a customary value, a precise list of the acts that can be recognized and acts that cannot is lacking. The so called “Namibia exception” gives the possibility to recognize some acts of an illegal authority in favour of the inhabitants of an occupied territory and international courts’ decisions referring to this exception have already been analysed. Therefore, I will focus on the national case-law related to this issue. In which circumstances does a domestic judge give legal effects to an act adopted by an authority born in violation of a jus cogens norm? Are national case-laws in line with international case-laws? For instance, do national courts make a reference to the “Namibia exception” like ECtHR does or do they rely upon other considerations?

I faced then several methodological questions. Some are more theoretical, other more practical, even if all questions are linked. On a theoretical level, the different questions can be summed up in one: what am I doing? Am I trying to determine a customary rule using domestic courts’ decisions as State’s practice (law creation)? Or am I using the case-law of the national courts as a subsidiary mean for the determination of rules of law (art. 38, par. 1, d, ICJ Statute) (law enforcement)? On a practical level, how can I find those national decisions? How should I select them? How broad/diversified must the material be to obtain significant results?

My current choices can be laid out as follows. The distinction between law enforcement and law creation functions of domestic courts is artificial. Every national court’s decision has both values (Anthea Roberts). After this assumption, one can follows a comparative international law approach. But such an approach seems less persuasive in order to determine the content of the positive duty not to recognize. This assumption also seems to make it difficult to follow the method promoted by the ILC’s works related to the determination of customary law.

This leads me to a less formal approach. Following the works of André Nollkaemper, I consider domestic courts as “a key component in the protection of the international rule of law [that] do not protect domestic law against international law, but protect international law against itself”. Therefore, I see domestic courts as State’s organs able to sanction a serious breach of a jus cogens norm. Thus, it doesn’t matter anymore whether the national court’s decisions rely upon an obligation originating from international law (ILC’s approach) or from national law (such as “public order”, for instance). As soon as a decision gives or denies any effect to an act of an authority born in violation of a jus cogens norm, it becomes relevant for my purpose.

Symposium 2021

On the 28th May 2021, the Belgian Network of Junior researchers in international law organised its first symposium on “The Persuasiveness of International Legal Argumentation”. On this occasion, members of the network were asked to reflect upon the methods they apply in their own doctoral research to maximise the persuasiveness of their legal argument.

The contributions presented by the members were very varied, ranging from a reflection on the interactive role played by legal scholars regarding their object of study (Antoine De Spiegeleir); to an emphasis on the historical aspects of private international law in order to persuasively address contemporary issues (Willem Theus); as well as a historical analysis of legal discourse in the nineteenth century international peace movement (Wouter De Rycke).

The contributors benefited from questions and from the enriching feedback of a panel composed of Prof. Andrea Bianchi and Prof. Anne Lagerwall. The discussions were moderated by our esteemed Network member Dr. Alexandra Hofer.

We are very pleased to share the papers of the three contributors enriched by the insightful discussions held during the symposium.

International Law, This Interactive Butterfly

Do international law scholars make law? “No”, says the mainstream view on international lawmaking. To support this answer, many refer to a now canonical analogy between international law scholars and lepidopterologists. Scientists who study (pink) butterflies, the argument goes, do not make butterflies, they merely study them. So how could international law scholars make international law ? If we are to be scientists—and most of us hold this label dearly—then we must act like ones and limit ourselves to studying international law, rather than making it.

I offer a counter-view to this mainstream understanding of international law scholarship by means of a thought experiment. Taking the comfortable butterfly analogy seriously, I question the attractive reduction of international law to an “objective” entity, which one can study from a safe distance.

What would happen to international law, our very own pink butterfly, if no scholar ever recognized it as pink? And what of a consortium of mischievous scholars who suddenly decide to claim that it is a blue butterfly, rather than a pink one, or, even more dramatically, that it is no butterfly at all ? Does it make sense to claim that our pink butterfly still exists, out there, although nobody views it or refers to it as such? I think not. Instead, I claim that our pink butterfly does not outlive our cognition: it depends on it.

The concept of “interactive kind”, developed by Ian Hacking, refers to specific objects of human cognition that are not indifferent to our cognizing them. Instead, these objects are affected by—and reciprocally affect—our using and classifying them, and they may even only manifest themselves as a result of our cognition. Applying this concept to international law helps explain the ambiguous relationship between international law scholars and international law. Hence this short paper’s exploration of international law as an interactive butterfly.

In showing that the butterfly analogy does not hold and should be discarded, I also identify avenues for further important research not only on the inherently creative nature of international law scholarship but also on corresponding thorny questions of power, responsibility, and checks and balances potentially necessary to curtain the influence international law scholars exert on their object of study. With this thought experiment, I shed light on the ambiguities of our field. The very nature of a doctoral (and any) research rests on one’s understanding of scholarship. Ultimately, an inquiry into the latter is also inevitably a challenge to the former.

Antoine De Spiegeleir (LLM Candidate at Yale Law School)

Bringing the Private back into International Law

To fully understand many of the present principles of international law, one needs to be aware of their full history, which encompasses both public and private international law. Alas, too often this is not the case. One can for example only truly grasp the concept of extraterritoriality today if one is aware that for a large part of history this was a normal international trading practice that entailed that foreigners of different ‘nations’ were allowed to have their own legal and court system ‘follow’ them abroad. The term nation was interpreted in a remarkably fluid fashion: it could be on the basis of religion, tribe, city, … . It was therefore common to find different nations living together in one city -often in special districts-, all under their own laws and with their own courts. Naturally, numerous private disputes occurred between persons belonging to different nations and these somehow had to be solved. Which court had jurisdiction and which law was to be applied in for example a case between a Lucchese merchant based in Bruges and a local Flemish supplier of wool? Such questions have been asked throughout the globe since the dawn of international trade and they have been solved in different manners throughout the ages until the present day.

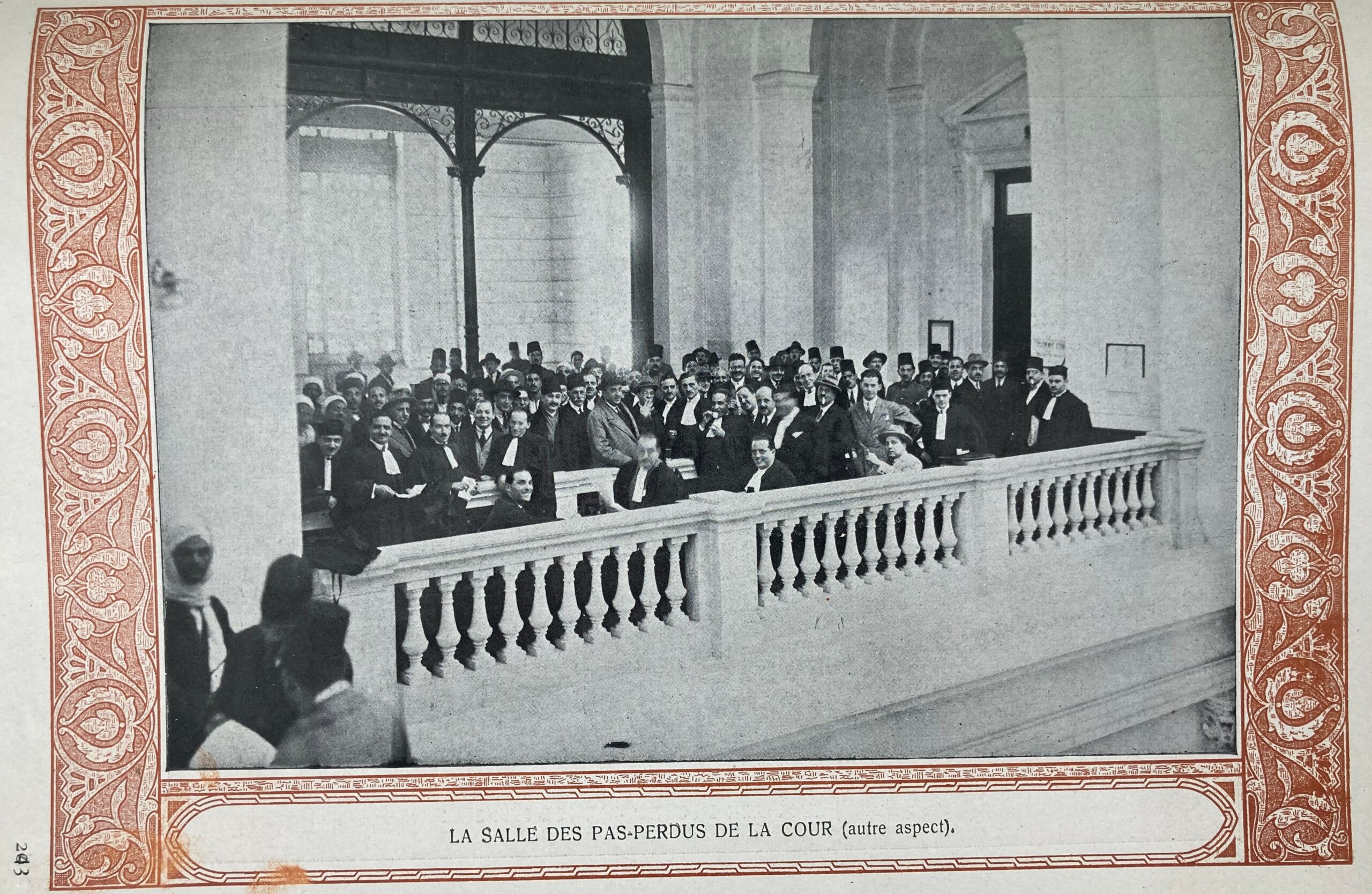

Two of such advanced systems to deal with disputes with a ‘foreign’ element form the centrepiece of my PhD research: the mixed courts of the colonial era and the contemporary international commercial courts. Both are remarkably similar, despite their completely different context. Both these court systems were/are very much ‘international’ in terms of their bench, bar, applied legal system, … yet they seem to remain completely under the radar for the (public) international law community. Whilst it is true that these court systems mostly deal with ‘private’ international matters, their impact and foundation is strongly connected to the ‘public’ international sphere. The Mixed Courts of Egypt (1876-1949) and of the Tangier International Zone (1925-1956) for example were both established by virtue of a treaty and were amongst the most successful examples of such ‘internationalised’ national courts, with many of those involved there going on to serve at the European Courts in Strasbourg and Luxembourg and elsewhere, taking with them their experiences of working in an internationalised court and legal system.

In the present, numerous states have established (and more are planning to do so) specialised courts to deal with complex commercial cases with a foreign element. Many of these international commercial courts employ foreign judges and easily (or by default) apply foreign law. These international commercial courts present a direct state-led challenge to the still-prevailing system of international commercial and investment arbitration, yet again they seem to be invisible in any public international law debate. It is therefore high time to bring back the private into international law. This 19th century division has been blinding us for far too long.

Willem Theus (PhD Candidate & Teaching Assistant at the Institute for Private International Law, KU Leuven)

Click here to download the full paper

How to defend Utopianism ?

Legal discourse in the nineteenth century international peace movement (1815-1873)

How should one study a ‘utopian’ ideology? Much of the history of the international peace movement in the nineteenth century is a story of failure. While the movement knew some limited success towards the end of the century, it never became the popular mass movement it sometimes pretended to be. For most decades of the nineteenth century, peace activism remained a small and rather elitist affair, composed mostly of bourgeois liberals, suffering from indifference or outright ridicule in larger society. This begs the question of how scholars should best approach any analysis of the legal instrumentation advocated by the adherents of the peace movement. Modern positive lawyers interested in the history of their discipline risk to overemphasize the contribution of pacifists to larger political developments, attributing influence where little could be plausibly found. They might also lose themselves in a highly conceptual analysis, resorting to abstractions and ideal-types that do not correspond anymore to the primary source material or the wider historical context. Conversely, historians like Skinner attach great importance to rooting out anachronisms, but can be accused of putting too firm a barrier between the past and the present.

Little as the peace movement may have politically accomplished prior to World War One, it cannot be disputed that modern-day public international law has deeply absorbed pacifist ideology. Whereas the law had for centuries given its sanction to the ultima ratio, the prohibition on the discretionary use of force by states is now one of the fundamental pillars of the world order installed by the United Nations. This fundamental shift in paradigm within international law has resulted from the confluence of many disparate longue durée processes, accelerated by two world wars. Legal historians have in recent years traced back the more immediate beginnings of this liberal-pacific turn to the professionalization of the discipline in the early 1870s. However, legalist anti-war thought goes back far earlier. While the peace movement may not have gained political traction in the nineteenth century, it did formulate a whole host of legal proposals, from arbitration to federative schemes, as well as set up an organization that attracted several prominent individuals. When the wind finally began to it blow in its favour during and after the Great War, the small pilot light kept alive by the earliest ‘friends of peace’ blazed high for the first time, finding expression in various legal instruments, like the Covenant of the League of Nations.

The extent to which pacifists actually contributed to these later developments, whether we are dealing with correlation or causation, is again up for debate, but this time far more likely than it had been for the earliest generations. Yet the purpose of ‘vernacular’ international legal histories should not be to explicitly expose direct genealogical links to the present, if not supported by the primary sources of the research period. Though it is theoretically possible to construct an evolutional history of any given legal notion, it is no necessary prerequisite for research into the intricate interplay of politics, law, and ideology in the middle of the nineteenth century, and, by careful analogy, beyond.

Wouter De Rycke (PhD Candidate at the Research Group Contextual Research in Law, VUB)